Dear Reader,

This is a monster of an essay because I’m attempting to combine multiple complex frameworks to try to understand the overarching societal evolution over the past 100 years. Even writing that sentence felt daunting. But it’s exciting to me, and I hope to communicate it in as easily digestible a way as possible.

Part 1 will be an overview of the psychological models I will be employing in our analysis, for readers who have little or no prior knowledge of them. But if you want to skip to the part where we get into the real work, just scroll down to Part 2.

As always, I welcome all feedback and dialogue. Now let’s get started!

The Setup

So what is this all about? And why have I been thinking about it?

Western society has made huge progress over the last century—in economy, technology, government policy, and more. What have also radically evolved are the major conversations being had in the cultural zeitgeist. Examples include the foreboding of nuclear war during the Cold War, the confidence of the Roaring 20s and experimental 80s, and the modern ‘woke’ movement.

But it’s hard to say if we have “progressed” in these conversations. Even if they are arguably more progressive and principled, the ways we go about having these conversations often feel like we’re stuck, or even sliding ‘backward.’ The same old conflicts flare up, albeit in different clothing, the same struggles for basic understanding and decency, and the same fears and divisions playing out on the global stage. In other words, are we getting wiser, or just getting louder?

Let’s call this the “societal/collective consciousness.” It's true there's a wide variety among individuals, but the zeitgeist of the collective at any point in time is mostly definable, and that's what we'll be exploring. Some may call it "the spirit of the age."

But I’ll be taking a unique approach to this analysis. Rather than using sociological theories, I’ll be drawing from models developed by psychologists originally meant for understanding the psycho-social development of individuals. What I’ll be attempting to do is take our understanding of how individual people develop and apply it to how societal consciousness has evolved.

The theories we’ll employ are:

Lawrence Kohlberg’s Moral Development

Jane Loevinger’s Ego Development

David Hawkins’ Map of Consciousness

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages

Now let’s get introduced to them.

Part 1: Understanding the Theories

Kohlberg’s Moral Development

Kohlberg’s model explains how we learn to discern right from wrong.

As kids, our first understanding of morality is as a matter of merely being rewarded or avoiding punishment (“Don’t steal the cookie, or you’ll get a time-out”). This is the Pre-Conventional stage.

As we grow, we start caring more about fitting in and being seen as “good” (“Good citizens follow the law,” or “What would my friends think?”). This is the Conventional stage, where morality is based on externally defined ethics.

Finally, some people develop a deeper sense of morality that is based on universal principles—things like justice, generosity, and human rights—even if that means questioning the rules everyone else follows. This is the Post-Conventional stage, and most people don’t develop into this area.

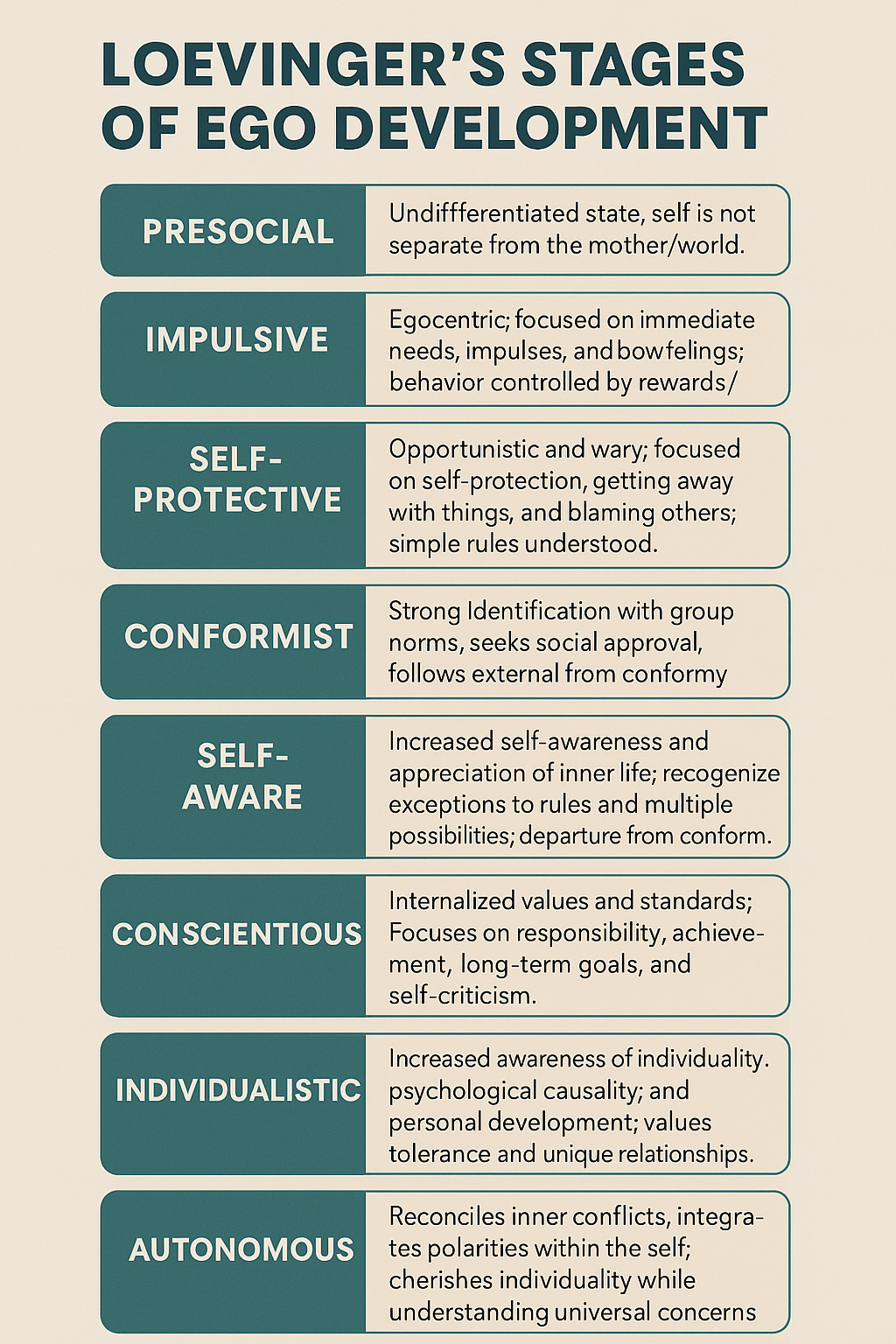

Loevinger’s Ego Development

Ego development is about how we make sense of ourselves and the world.

Loevinger saw a path starting from a very basic, impulsive stage (“I want it NOW”). Then we learn to be a bit more strategic, looking out for ourselves (“What’s in it for me?”). A huge chunk of development involves learning the rules of the group, wanting to belong and conform ("What does the team expect?").

Later, hopefully, we start developing more self-awareness, questioning those norms, forming our own values ("What do I truly believe?") in the Conscientious stage.

In this stage,

a person’s moral framework moves from being externally motivated to internally determined,

they begin to conceptualize themself as an individual apart from the group,

they prioritize whole-system effectiveness and objectivity,

they focus on measurable reality, laws, control, results, and goals,

and identify with ideology (as opposed to groupthink).

We eventually, but rarely, become more comfortable with complexity, paradox, and seeing things from various perspectives in the Individualistic and Autonomous stages.

In the Individualistic stage, a person

recognizes and respects individual differences, complexities of circumstances, and autonomy,

recognizes subjective experience and inner conflict of being a unique individual with many selves,

prioritizes inner reality to objective reality.

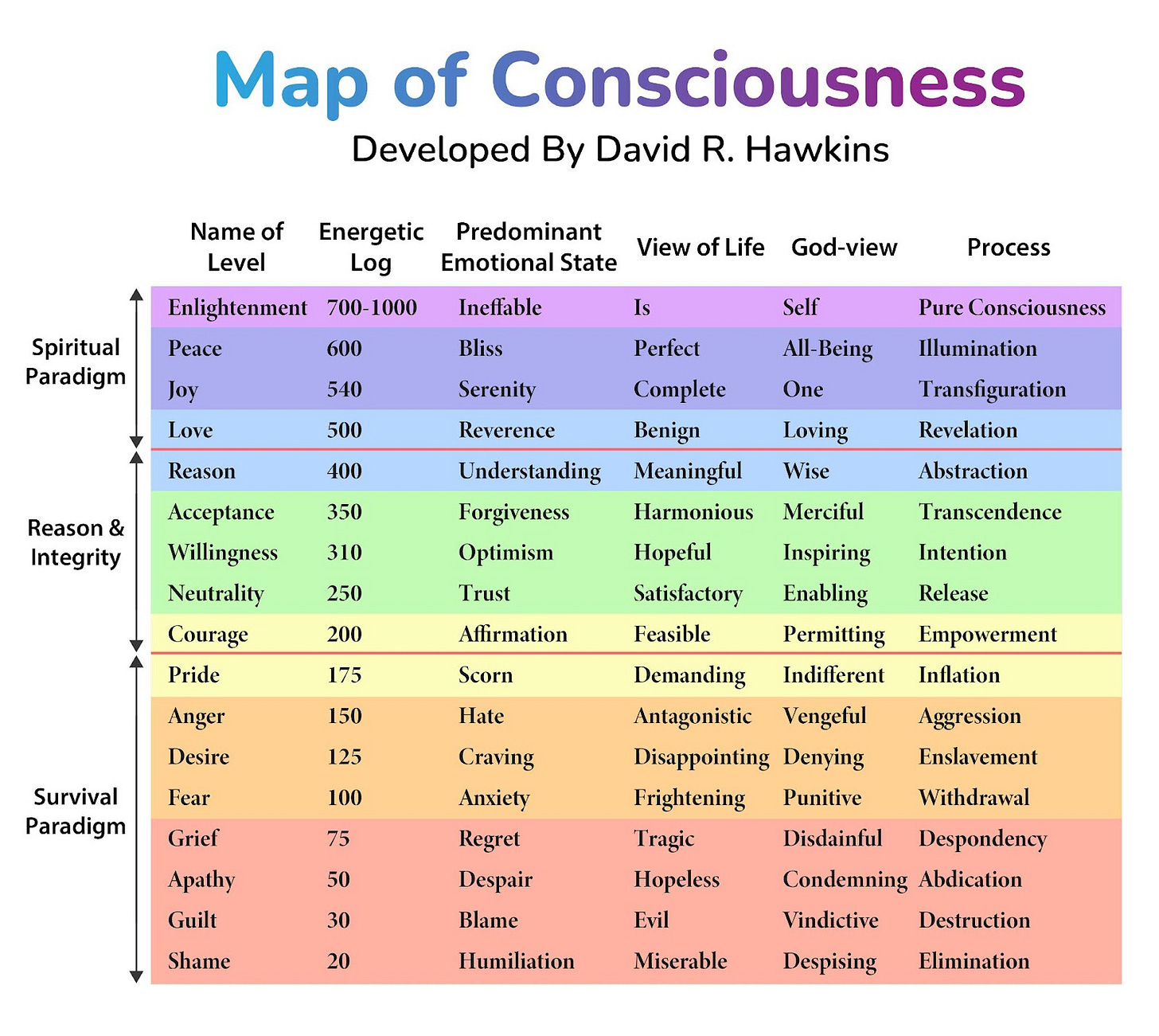

Hawkins’ Map of Consciousness

Hawkins took a unique approach. He linked levels of human awareness to dominant emotions, creating a kind of vibrational scale:

At the bottom are heavy, constricting feelings—states where life feels like a constant struggle. As consciousness expands, you move up from survival mode into a place where you operate from reason and acceptance. Most people are here. Higher still are expansive spiritual states of love, joy, peace, and eventually enlightenment.

Later, we’ll see how it’s not just individuals, but entire societies that tend to operate predominantly at certain levels on this map.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages

Erikson said we move through eight stages across our lifespan. Each stage presents a core challenge ("crisis") that we need to navigate to grow healthily.

It starts right from infancy (learning trust vs. mistrust), moves through childhood (developing autonomy and initiative), adolescence (figuring out identity vs. role confusion), adulthood (generativity vs. stagnation), and finally, old age (looking back with integrity vs. despair). He showed how successfully navigating these life tasks shapes our personality and our ability to function well in the world.

Maybe as you think about the adolescent stage of Identity vs Role Confusion and the young adulthood stage of Intimacy vs Isolation, you’re starting to think of the major struggles facing our society today?

Okay! So that’s a lightning-fast intro to the lenses that will make up our multifaceted perspective in this exploration of our collective conscious development.

Now let's put them to work. What happens when we use these frameworks to look back at the trajectory of society, say, from the beginning of the 20th century until now? Can we see patterns? Let's start by diving into the tumultuous world of the early 1900s…

(Time for a good chunk of history)

Part 2: Applying the Models to History

Mindset in the Early 20th Century (1900-1945)

Coming out of the previous century's industrial progress and cultural confidence, this half-century fundamentally shook the world. Simmering tensions and unfortunate global alliances exploded into WWI. Millions perished, empires crumbled, and a generation was left reeling.

Then just as folks were trying to pick up the pieces and maybe dance the Charleston a bit, the bottom dropped out with the Great Depression. All certainties of progress vanished and survival became the grim focus for vast numbers of people worldwide.

And out of that fertile ground of fear and despair rose the authoritarian regimes. They promised order, restored glory, and easy scapegoats, feeding on the anxieties of the time.

All this culminated of course, in the horror of WWII. It was an era of rigid social norms, expectations about class, race, and gender, alongside unimaginable upheaval.

If we had to pin down the dominant moral frequency of this era, I think it would largely resonate with Kohlberg's conventional level: morality is determined by law and order, and your concern is to be a "good boy/nice girl." What mattered most was obedience to authority, whether that authority was the nation, the church, the military commander, or the head of the household. Nationalism was a powerful force, often overriding individual conscience ("My country, right or wrong"). Strict social hierarchies were generally accepted as the natural order of things. Duty, sacrifice for the group, and maintaining the existing social structure were paramount moral goods.

The societal center of gravity also seemed firmly planted in the Conformist stage (Loevinger), where belonging was crucial, and you defined yourself by your roles—soldier, mother, worker, member of X community. There was a strong sense of "us" versus "them."

Not surprisingly, this era felt heavily anchored in the lower frequencies of Hawkins' Map of Consciousness. Fear of invasion, fear of starvation, fear of the secret police. There was anger bubbling up in nationalism, scapegoating, and revolutions. Life often felt like a struggle for survival.

For young people coming of age amidst war and economic collapse, the challenge of Identity vs Role Confusion became incredibly acute. How do you forge a stable sense of self when the future is so uncertain? The "Lost Generation" after WWI is a classic example.

Now, there were flickers of something else. The suffrage movements for women's rights and pacifist voices questioning the war machine showed early signs of post-conventional thinking (Kohlberg), arguing for universal principles that transcended the current rules. Some people were driven to deeper self-reflection where they might begin to develop their own internal compass, signs of the Self-Aware stage (Loevinger). The pressures of this era also saw many demonstrating Courage (Hawkins), the crucial first step out of victimhood and towards agency.

The early 20th century looks like a society largely operating out of a need for order, belonging, and basic survival, often driven by fear and anger. Morality was mostly about following the rules, and identity was tied closely to prescribed roles. But the very intensity of the era's challenges also contained the seeds for change, pushing some individuals and groups to question, to strive, and to reach for something beyond the status quo. The pressure was building, and things were about to shift again.

Questioning and Rebuilding in the Mid-Century (1945-1980)

This was a period of significant economic growth often called the "post-war boom." But hovering over everything was the Cold War. The ideological battle created a constant, simmering tension, punctuated by proxy wars (like Korea and Vietnam) and the terrifying threat of nuclear annihilation. "Duck and cover" drills became a bizarrely normal part of childhood for many.

Yet, something was stirring. This was the era of major civil rights movements, like racial justice and early feminism. Simultaneously, countercultural movements like the hippies, rock and roll, and other groups questioned traditional values about work, family, sexuality, and authority.

It was an era marked by both rebuilding old structures and challenging established norms. We see a surge into post-conventional morality (Kohlberg), where right and wrong is defined by principles and ideals. The Civil Rights Movement is a prime example of arguing from a place of universal ethical principles and civil disobedience. Others include the anti-war movements. People weren't just asking "Is it legal?" but "Is it right?" That's a post-conventional leap.

The push beyond mere conformity resonates with Loevinger's Conscientious and Individualistic stages. People started developing a stronger internal compass, evaluating rules and roles based on their own values rather than just accepting them wholesale. The focus shifted towards self-awareness, psychological understanding ("finding yourself"), and appreciating individual differences. Not everyone reached these stages, but the cultural ideal moved towards individuality rather than fitting in. Think of the shift from the "organization man" of the 50s to the more individualistic seeker of the 60s and 70s.

There's a palpable sense of rising energy during this time. The post-war optimism, the economic expansion, the "can-do" spirit reflect a move towards Willingness and Acceptance (Hawkins). However, this upward trend wasn't smooth. The fear of nuclear war and the anger of ideological conflicts were a constant drag, pulling the collective consciousness back down. It was a push-and-pull between hope and fear, progress and paranoia.

With the basic survival threats lessened for many compared to the previous era, Erikson's stage of Generativity vs. Stagnation came into sharper focus for society as a whole. This stage is about contributing to the world and guiding the next generation. There was a drive to build stable communities, invest in education, create social programs, and fuel innovation. The activism of the era also was a form of generativity—actively trying to shape a better society for the future. The flip side, stagnation, was the resistance to change and a sense of cynicism and disengagement.

So the mid-20th century was a complex mix. It was an era of great building and great questioning. Society seemed to be collectively wrestling with its conscience, pushing towards higher ideals of justice and individual expression, and generating immense energy for change. But the shadows of fear and conflict lingered, setting the stage for the even more complex, interconnected world that was about to emerge.

Acceleration and Anxiety in the Late 20th & Early 21st Century (1980-Present)

Now we arrive at the era we're all swimming in. If the mid-century felt like shifting tides, this period feels more like a high-speed washing machine.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War ushered in a wave of globalization. Goods, money, ideas, and people started moving across borders like never before, breaking down once-clearly-defined categories.

Then came the digital revolution that rewired how we communicate, work, shop, and even think. Information suddenly travels at light speed.

But this interconnectedness brought new anxieties: fears of climate change; the shock of 9/11 and the subsequent "war on terror"; economic booms and devastating busts; political polarization.

And just when we thought things couldn't get wilder, the pandemic hit. It laid bare our deepest societal fault lines.

It's an age defined by breathtaking complexity, instant connection, and a pervasive sense of anxiety and uncertainty.

In true fashion of our time, it's harder to pinpoint where we are on the maps/stages of the various models we've been using so far. Things are getting really interesting and messy:

On one hand, we see clear expressions of post-conventional morality through movements based on ideals like human rights, equality, etc. However, on the flip side, political conflicts feel more like tribal warfare, relying on appeals to group loyalty (conventional), or even self-interest and power dynamics ("might makes right," pre-conventional). The deliberate use of disinformation and the demonization of opponents aren't hallmarks of high moral reasoning. So it feels like society is being pulled in both directions: reaching for universal principles while simultaneously getting dragged back into more primitive moral frameworks.

Similarly, the sheer complexity of modern life demands higher levels of ego development. There's a greater need than ever to handle ambiguity, appreciate diverse perspectives, and develop systems thinking (Autonomous and Integrated stages). These people are less driven by simple rules or group pressures—and indeed, we see many individuals operating at these sophisticated levels. But... the echo chambers of social media, economic stress, and information overload reinforce Conformist thinking, black-and-white worldviews, and sometimes even Self-Protective stages (us vs. them). It's as if the potential for higher development is there, but the environment often pulls people back towards less complex, more defensive ways of making sense of the world.

We see moments of incredible global solidarity, especially during natural disasters or the initial phases of the pandemic where communities came together. These moments touched on Love and shared humanity and altruism. Yet, the lower frequencies remain stubbornly persistent. Fear is amplified by 24/7 news cycles, social media algorithms, climate warnings, and "the other." Anger fuels political divisions, online mobs, and ongoing wars. The static and interference from the lower frequencies of consciousness are incredibly strong. We oscillate, capable of great empathy one moment and intense division the next.

Looking through Erikson's lens, the societal focus seems increasingly drawn to the final stage: Ego Integrity vs. Despair. Faced with existential forces from pandemics to globalization and AI, we are forced to ask: What does it all mean? Can we find a sense of collective purpose and coherence (Integrity) in the face of them? Or do we succumb to fragmentation and cynicism (Despair)? The search for meaning, for a narrative that makes sense of our complex present and offers hope for the future, feels like a central psychosocial task for society right now.

So where does that leave us? The late 20th and early 21st centuries show a society capable of incredible sophistication in its thinking, moral reasoning, and potential for connection. Yet, at the same time, we seem incredibly vulnerable to fragmentation, fear, regression, and despair. The highs are higher, but the pulls downward are perhaps stronger and more insidious than ever.

The Story So Far

Okay, so we've taken a whirlwind tour through the last century or so, peering through the lenses of these fascinating developmental theories. We've seen society grapple with world wars, depression, rebuilding, social upheaval, technological explosions, and global crises. Let's take stock of the major themes we've uncovered:

A General Drift Towards "Higher" Stages: Despite all the bumps, there does seem to be an underlying current pushing towards what these models describe as more developed stages.

Kohlberg: Shift from rule-based, authority-driven thinking towards appeals to universal principles—even if we argue about what those mean in practice.

Loevinger: Move from conformity to individuality and the capacity to grapple with complexity and nuance. The "examined life" is more of a cultural ideal than it used to be.

Hawkins: While fear and anger are still prevalent, the cultural conversation and aspirations have increasingly progressed towards acceptance, reason, and even love.

Erikson: Societal challenges have evolved from basic identity formation to meaning contribution, and now, finding collective integrity in the face of existential threats.1

Increasing Complexity Demands Higher Development: Globalization, instant communication, and god-like technology require more sophisticated ways of thinking. Simple, black-and-white, rule-based approaches just don't cut it when dealing with multifaceted global problems that have no easy answers. Coping with ambiguity, understanding diverse perspectives, and thinking systemically become necessary skills. We need to push ourselves towards those higher developmental capacities.

Persistent Polarities Between "Higher" and "Lower": For every sign of post-conventional morality, there's a resurgence of tribalism. For every call for nuanced understanding, there's the pull of simplistic echo chambers. For every glimpse of love and solidarity, there's an undertow of fear and anger. Progress in one area might coexist with regression in another. We seem capable of holding incredibly sophisticated ideas about human rights while simultaneously engaging in dehumanizing behavior. We develop technologies that connect the globe while feeling more fragmented than ever. It's a real paradox.

This tension, this push-and-pull between higher potential and lower-stage drags, can be better understood from the perspective of one of the most powerful, yet often overlooked, forces in this whole cosmic drama. What happens when the parts of ourselves we've ignored, suppressed, or denied start bubbling up to the surface? Let's dive into that.

The Shadow

There's something that often lurks just beneath the surface of all this talk about progress and development: the "shadow." It's a concept psychologist Carl Jung talked about a lot regarding individuals, but it applies extremely well to societies too.

Think of the collective shadow as everything a society tries to ignore, deny, or shove under the rug about itself. It's the uncomfortable truths, the unresolved traumas, the nasty impulses, the hypocrisies, the bits we don't want to admit are part of "us." Like a personal shadow, the collective shadow doesn't go away just because we ignore it. In fact, the more we suppress it, the more power it gains, often erupting in unexpected and destructive ways.

Looking back through our historical periods, we can see the shadow playing different roles:

In the early 20th century, the shadow was suppressed. There was a strong tendency to maintain appearances, uphold rigid norms, and pretend certain realities didn't exist. This shadow consisted of the unprocessed, collective trauma of the world wars. A generation scarred, yet often met with a stiff upper-lip mentality that did not grieve or question well.

Suppressing the shadow is like holding a beach ball underwater: eventually it will burst up with force. The repressed fears, resentments, and traumas festered, and they erupted in the form of extreme ideologies like fascism, which exploited them, offered scapegoats (projection), and promised a return to order.

In the mid-20th century, the shadow was confronted. While suppression certainly continued, certain things were brought into the light. Colonialism and racial injustices were forced into public awareness by the civil rights movements, and other countercultural movements addressed sexuality, materialism, and blind faith in authority.

This confrontation was messy, painful, and violent. But crucially, it was an attempt to see and engage with things that were festering underneath. It was the beginning of trying to integrate the shadow, however imperfectly.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, the shadow was caught in a tug of war. Today, our relationship with the collective shadow feels more dualistic and confusing. We are simultaneously more aware of societal shadows than ever before, yet also incredibly adept at creating new ways to avoid or deny them. It's a constant tension between confrontation and sophisticated avoidance.

We are festering intense emotions about economic pressures and disparity, overwhelming mental health issues, uncertainties about new technology, the erosion of privacy, and what to do with historical injustices.

Our awareness is high, and desire for progress, love, and unity is strong. But powerful forces are trapping us in conformity, tribalism, and fear-based consciousness when the shadow feels too overwhelming.

Understanding this shadow dynamic is crucial because it helps explain why progress feels so uneven, why societies seem to oscillate between insight and blindness. The shadow contains energy and potential for a healthier society for all, but if left unintegrated, it continues to trip us up and pull us back as we try to move forward.

But sometimes, attempts to integrate the shadow don't go well...

The Lash... and the Backlash

As we became more sophisticated in our thinking—as we progressed towards more nuanced, principled, and individualistic worldviews—we started taking the complexities of subjective experience more seriously. Maybe it was the horrors of the wars that made absolute beliefs seem dangerous. Maybe it was encountering other cultures more directly through globalization. Maybe it was advancements in psychology and social sciences highlighting how much our context shapes our views. Whatever the exact blend of reasons, we started to deconstruct the idea of one-size-fits-all rules and realities. We moved into an age where relativism ruled over the single-system framework.

Now, let's pause for a moment: from the perspective of our developmental theories, this initial movement had a lot going for it. It required moving beyond mere Conformity (Loevinger) to acknowledging multiple perspectives and even embracing ambiguity. It challenged societal norms and asked how we can make the world better for everyone.

This evolved into an awareness of the marginalized, exploited, and overlooked. People started pointing out that the old "universal" truths and rules often weren't universal at all—they were usually the truths and rules of the dominant group, and others who didn't fit had been dismissed, silenced, or distorted.

So a movement began to challenge the lingering vestiges of society's older frameworks. In its essence, this drive for inclusivity and the recognition of diverse realities could absolutely be seen as a step forward in the development of our cultural consciousness. It represented an attempt to broaden our understanding, to integrate perspectives previously left in the shadows, and to build a potentially fairer, more empathetic world. It felt like we were finally trying to grapple with the true complexity of human experience.

But... like many powerful movements, things didn't necessarily stay on that initial, promising track. Things started to feel a bit... off.

Born from a desire to dismantle rigid dogma and challenge tribalism, this movement began to develop its own rigid dogmas. It became the very thing it had set out to challenge—and maybe even worse.

The movement that challenged exclusion became exclusionary. The voices that were once suppressed became the suppressors. The ones who decried group privileges adopted tribalist, "us vs. them" behavior. And the proponents for diversity became resistant to nuance and flattened complexity into simplistic narratives of oppressors and oppressed.

Instead of fostering tolerance for ambiguity (a hallmark of higher development), it demanded strict adherence to a new set of orthodoxies. What started as a call for empathy morphed into policing language and punishing perceived transgressions. It felt less like an invitation to deeper understanding and more like a new form of social control, wrapped in the language of liberation.

We saw the movement turn pathological. And you know the rest.

Naturally, when you push hard in one direction, society shoves back. And shove back it did. People got tired of walking on eggshells, intellectual straitjackets, and the intolerance emerging from the movement supposedly championing tolerance.

So, symbolized by the return of Trump, we are now kicking it back out, stuffing it back down—and returning to the Conscientious stage's objective standards, established procedures, and control of the system. People longed for clearer rules and less ambiguity again.

In many ways, the resulting culture wars revealed that both sides, while claiming to possess higher levels of consciousness, reason, and morality, frequently exhibited characteristics of lower levels of development. Both resorted to in-group vs. out-group dynamics (Loevinger); both forsook empathy, perspective-taking, and understanding of complexity (Hawkins); both fell back onto moral reasoning based on reward/punishment or external motivation (Kohlberg); both were dominated by lower emotional states of fear, anger, and resentment (Hawkins).

The very conflict became evidence that perhaps neither side had fully achieved the level of development needed to handle the complexities they were fighting about. This brings us to a deeper, psychological way of looking at what might have happened.

When the Shadow Takes the Wheel

The uncomfortable truths about historical injustices, the experiences of those previously silenced, the questioning of dominant narratives, these were precisely the kinds of things society had preferred not to look at too closely. They were aspects of our collective shadow. Thus, this movement could be seen as the shadow demanding attention, knocking on the door of consciousness, calling for reconciliation and integration. Bringing these hidden parts into the light is, theoretically, essential for growth towards wholeness, both for individuals and societies.

However, it wasn't a healthy emergence at all, even if the content needing to emerge was valid. It wasn't a carefully managed process of integration. It was an eruption, a lashing out of what was repressed. This is why it exploded in 2020-21: the collective psyche's intense stress and anxiety during the pandemic was the crack the boiling, festering energies beneath took advantage of. The anger, the chaos, and the sudden overturning of established norms were deeply destabilizing.

Now, let's borrow from individual psychology for a moment. Jung talked a lot about what happens when the personal shadow unexpectedly breaks through into a person's conscious awareness. Suddenly, you're confronted with feelings, memories, or truths about yourself you've long denied. What happens next largely depends on the strength and maturity of the person in whom this cosmic drama is taking place: their ability to manage reality and integrate difficult experiences.

If the person has a healthy, mature ego, they might still feel shocked, disturbed, maybe even ashamed. But they have enough resilience to face the shadow material without completely falling apart, and find a way to temper, reconcile, and eventually integrate the tumultuous shadow.

But if the person has a fragile, fragmented, or undeveloped ego, the shadow can be utterly overwhelming and effectively take over, leading to impulsive acting out, becoming possessed by the very traits they previously denied, projecting the darkness wildly onto others, shattering their sense of self, or retreating into rigid, defensive postures to desperately regain control. The encounter leads to more fragmentation, not wholeness.

The problem is, when the shadow emerges in an eruption, it's usually because it has been repressed by a fragile, underdeveloped ego. Then, since the eruption is often destructive, the ego has more reason to bring down the iron hammer and send it back to the abyss from whence it came. The confrontation is aggressive and judgmental, and it leads to defensiveness and resistance rather than integration. An understandable response for sure, but terrible for both aspects of the psyche—and that's what we've been seeing in the culture wars.

This leads us to the ultimate question : If our grappling with deeper complexities and shadow material essentially blew up in our faces, does that mean we as a society are not ready and equipped to handle the next stage in our psychological development?

Watching society reach for higher ideals only to get tangled in its own shadow and retreat into culture war bunkers, it makes me wonder...

So... Have We Peaked? Are We Stuck Here?

Maybe we aren't ready to evolve into a consciousness of greater ambiguity, nuance, and tension. Again, there is a wide variety of people at different stages of development—which is why we feel this push-pull dynamic in our cultural conversations. We just aren't talking to each other at the same frequencies.

Maybe holding multiple conflicting truths simultaneously, having empathy for people we profoundly disagree with, acknowledging our own shadows without getting defensive or collapsing... maybe that's a developmental leap we haven't managed to stick the landing on, collectively speaking.

But maybe progress has, and still can, be made. Perhaps we are in a phase of recalibration where we have gained greater awareness of where we've fallen short, the wounds we've covered up, and the need for evolution. Perhaps the culture wars, painful as they are, signals a deeper wrestling with issues that previous generations could more easily ignore. We know things are complex now, even if we struggle with how to handle that complexity.

The core concerns raised by the collective shadow can still be reframed and re-addressed. We’ve maybe learned, the hard way, that integrating the shadow and embracing multiple perspectives requires more than just good intentions; it requires immense psychological maturity, robust communication skills, and strong containers (both individual and societal) to handle the inevitable friction. We might have learned that how we engage with these difficult truths matters just as much as the truths themselves.

It's true that facts don't care about your feelings. But your feelings don't care about facts either. And if you, I, and everyone else are to move forward, we must find a mode of interaction between opposing forces that encourages integration, not retaliation.

But there's something else that gives me some optimism. Even amidst the pressure to pick a side, the culture wars have produced a growing number of people who hold no loyalty to either ideology.

They aren't necessarily organized. They don't have a catchy name or fly a specific banner. But you can spot them by their approach. They are determined to wade through the muck and grapple with multiple, opposing perspectives. They accept that the world is messy and contradictory.

These people tend to be better at tolerating ambiguity, polarity, and dissonance. And they operate with a degree of humility. Does this sound familiar? It should, because these are the very characteristics of the higher stages of psychological development.

I am hopeful because these individuals are navigating the stormy seas, charting a course between the Scylla and Charybdis of dogma on either side. They might not be the loudest voices (in fact, they often aren't, because nuance doesn't make for great clickbait), but they are demonstrating in real-time the kind of thinking and relating that can potentially move us higher and deeper.

I must make a note here of the irony. While we indeed are grappling with late-stage generativity and integrity, we are also struggling with identity as a basic concept, particularly among the young. I think that we have come full circle in Erikson's stages—completed the life cycle, so to speak—and will be experiencing a collective "rebirth" soon.

Wow. What a synthesis of models. The core makes perfect sense to me. I'll be going through it again but wanted to give you kuddos for tackling big, meaningful ideas. I enjoy the way you think. Thank you for sharing.

Nathanael, excellent job at taking such a large amount of complex thoughts/frameworks and organizing them in such a way that's logical and flows well. I like the approach of "here's all the pieces; let's put them together in these different ways." There was definitely quite a lot to unpack here.

I do find it striking how hard times like war, disease, or tyranny can knock societies down several pegs and keep us stuck around the self-protective stage.

Your thoughts on shadows here also intrigue me. I do think that we as a society have done rather poorly handling the shadows brought about by the Cold War, 9/11, COVID, etc. This being said, it does seem like some younger people are recognizing the patterns and addressing them.

On the thought of holding no loyalty to a particular ideology, this does make me think about the so-called "swing states" that we have here in the USA. These states don't reliably vote red or blue like most other states; they change between elections and depending of the circumstances. I like to think this is because the people that live in these states tend to live at the higher stages of ego development than those of the other states. Because of this, it's the swing states that decide the outcome of the election, for the most part. People seem to want to pay attention to the more nuanced thinkers rather than those who reliably think the same thoughts over and over again.

Personally, I've spent most of my childhood and adolescence in the self-protective and conformist stages; I had such an awful time there mainly due to my neurodivergence. I never fit in with any groups of people well nor did I have any close friends. Only after having tried to fit in with everyone else failed so miserably did I start to not care about what other people think, doing what I thought was best for myself instead. In essence, I slowly began to climb up the stages. This is when life started to improve for me. Even on the rare occasions that the shadows appear, I tend to handle them decently well.

Very nice work here!